As part of our Product Hero, Design Leader, and Product Innovation series and for the book Product Leadership we’ve interviewed hundreds of product and design leaders. Throughout these interviews, one thing matters more than anything else.

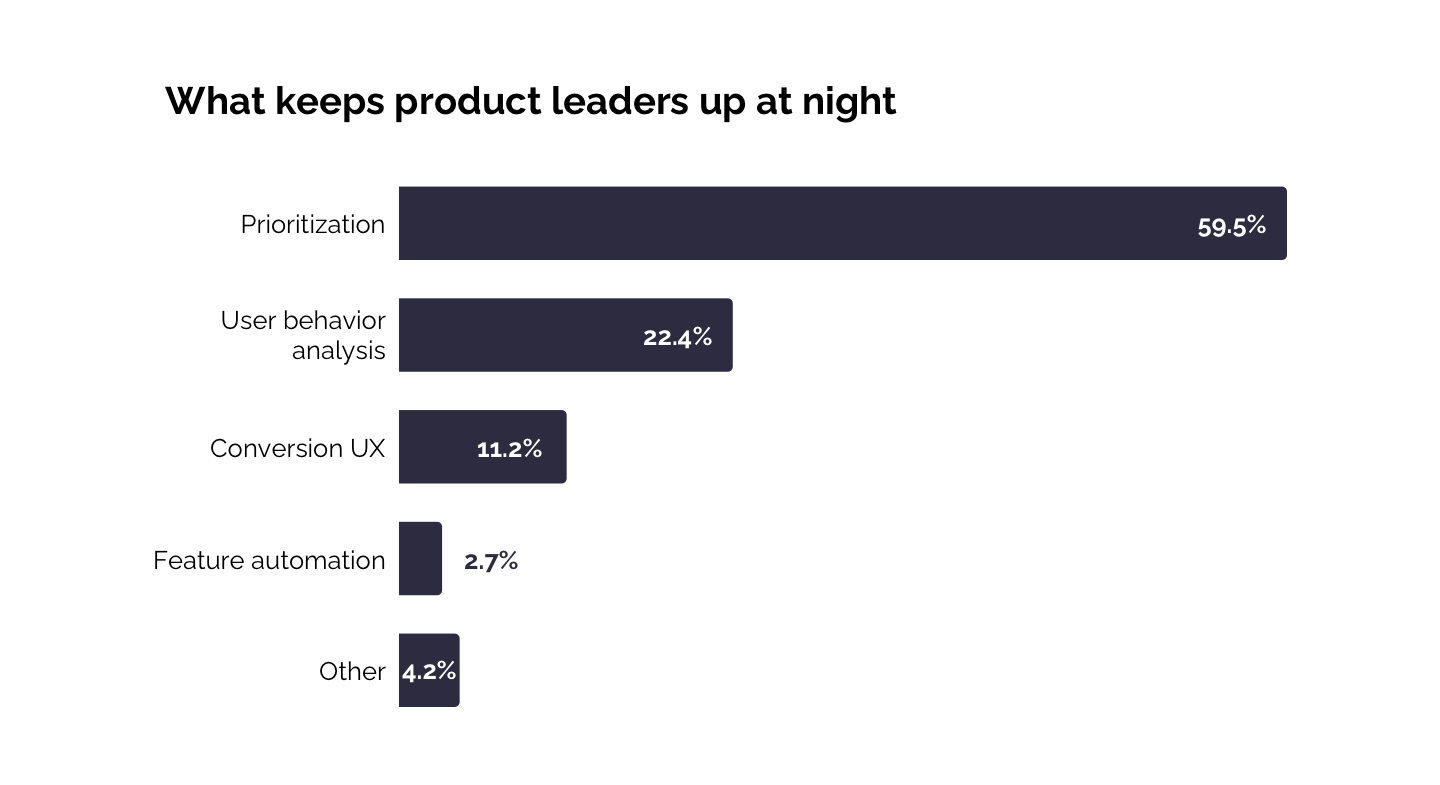

To see if this one thing held true for an even larger sample we ran several polls and surveys. We asked product and design leaders just one question:

What’s your biggest challenge right now?

The results were pretty clear: The biggest challenge to getting things done is knowing WHAT to get done — prioritization.

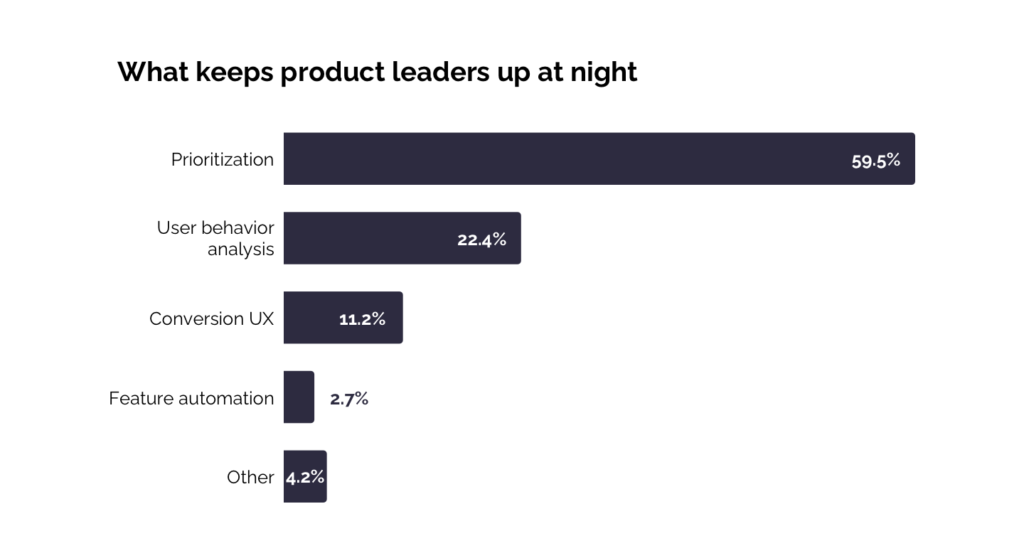

Prioritization comes out on top even when you ask product and design leaders to rank the relative importance of these challenges on a scale of 6 (trumps everything else), to 1 (not important). Prioritization reigned supreme even when we added “existing and new product innovation” to the list of possible responses.

Why Is Prioritization So Hard?

At the most basic level, choosing one thing over another means saying ‘no’ to someone. That someone might be a customer, a salesperson or a board member. It doesn’t matter who you’re saying ‘no’ to, it’s still hard to do.

Product gurus like Rich Mironov, Ken Norton and Martin Eriksson have written about why product leaders are responsible for product success without having the requisite authority to drive those decisions through the organization.

Related to this is that product leaders don’t always have enough resources to knock down everything that’s on the product ToDo list. Getting the valuable resources you need can feel like horse-trading with the rest of the organization. Suddenly prioritization feels more like politics than business.

Lack of time is actually lack of priorities. — Tim Ferriss

If product leaders do not have the final say on prioritization, how are some frequently shipping experiences while others are mired in indecision and politics?

A Path To Sustainable Prioritization

Here’s what we know from the hundreds of interviews with successful product leaders: 1) prioritization is impossible without a clear vision, and 2) feature roadmaps aren’t enough, you need to prioritize & roadmap across marketing, product, engineering, and sales.

Phase 1: Aligning The Product Organization To A Vision

Priorities don’t exist in a vacuum. Leaders and managers can only rank their tasks and efforts by where they are headed. Like any journey, a clear, meaningful destination makes the individual steps infinitely easier.

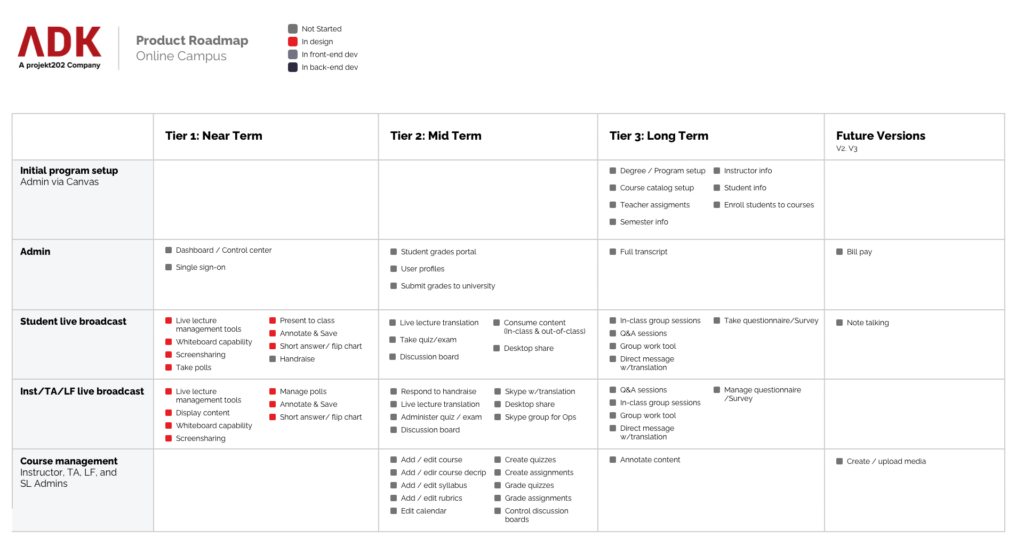

Creating a vision to align the organization to isn’t easy, but the process is straightforward. I recommend starting with the Radical Product framework. Below is a taste of the Radical Product output and how it’s used to prioritize features and effort.

You can see from the quadrant above that having a vision helps address market fit and sustainability concerns. As we’ll see in a minute, it also provides product leaders with a powerful tool to tackle thorny political conversations.

The vision should be aspirational and unattainable, but it allows everyone on the team to connect with a higher goal, a purpose they can believe in”.— Nate Walkingshaw

Put another way, it should help you, your team and your customer visualize what this better world looks like.

Phase 2: Aligning Vision With Strategy and Roadmaps

If the vision is the horizon, the True North, then the strategy is the map that sets out the path from where you are today to that horizon. The strategy shows the incremental steps in delivering product experiences and to which customer segments.

For the strategy to deliver on this promise it must, at the very least, answer these four questions in a way even your grandma will understand:

- Who is product for and what pain will they solve with this? (market fit)

- What are the recognizable features or elements that make your product valuable and remarkable? (design and brand)

- Why is this company uniquely capable of delivering this solution? (defendable capabilities)

- How will this be delivered to the end user? (logistics)

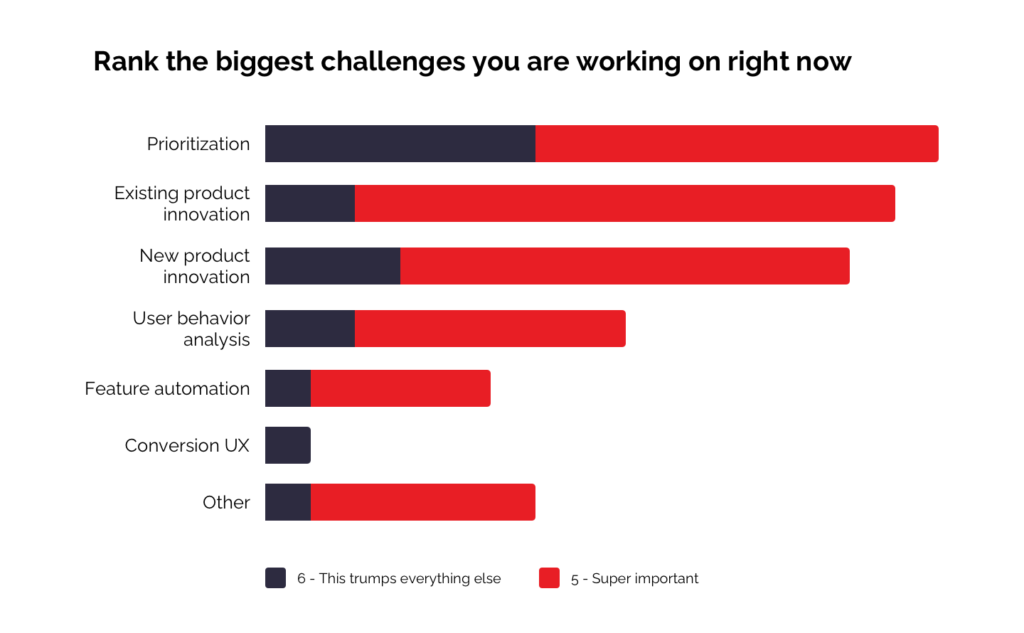

Once you have solid answers to these questions you can move onto developing a product roadmap. The roadmap comes from taking the answers to the questions above and ‘mapping’ them to the time periods Now (or Near term), Next (or Mid Term), and Later (Long Term). The exact headings are less important than the intention to provide a temporal theme to the work.

A final word on roadmaps. These are not release plans, user stories, JTBD or feature lists. As C Todd Lombardo says they are a strategic communication artifact that conveys the path you’ll take to fulfill your product vision.

More often than not, the lack of a roadmap encourages you to do too many things not as well. — Anthony Accardi, CTO of Rue La la

For a more detailed approach to roadmaps I recommend reading Relaunching Product Roadmaps: How to Set Direction while Embracing Uncertainty.

Phase 3: Develop Proof Points

As you make a case for your roadmap, you’ll find yourself pitching why one feature needs to be included at the expense of another. A powerful way to legitimize your priorities to customers, senior decision makers and team members is to create a prototype.

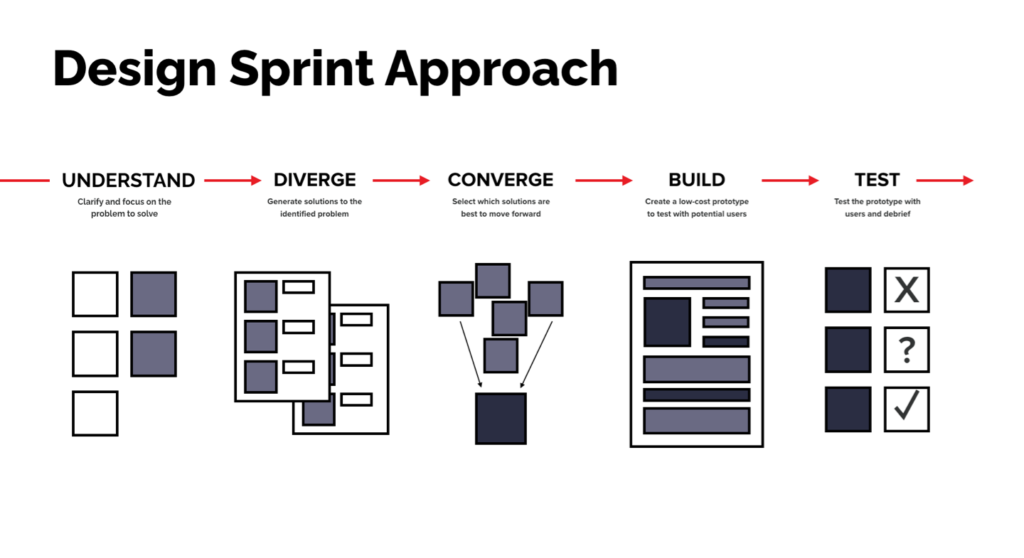

Prototypes are testable and generate real data. Validating a new feature or interactions demonstrates objective proof and market need. The easiest way to do this is with a Design Sprint or Directed Discovery.

Source: Design Sprint: A Practical Guidebook for Building Great Digital Products

Demonstrating the data behind the design decisions reduces the potential for negative influence an executive, salesperson, or subjectively focused customer might assert on the priority.

When the team invites real users to try a prototype, they’re collecting data about the users’ needs, which provides a solid footing for the design. — Jared M. Spool

The most successful product managers are nailing all three of these phases. Having a clear vision that’s aligned with a focused strategy gives them a roadmap to prioritize their team’s efforts.

How Prioritization Makes Product Leaders Better

Connects Vision To Practice

Linking the product vision to the practical work might feel too etherial when you’re trying to meet a shipping deadline. In contrast, taking the time to make this connection makes the work easier to understand for everyone, and saves time in the long run.

Reminding the team why you’re building that feature or making that improvement gives the work meaning and can be motivating.

A big part of product leadership is thinking about why are we doing this-and-that to set the basis for saying no, we shouldn’t do that. — Mina Radhakrishnan

What not to prioritize is as important as what you’ll be prioritizing. The vision serves as a filter to de-prioritize the things that won’t make a meaningful difference to the value of the product or experience.

Shuts Down Out-of-Nowhere Requests

The reality is that stakeholders asserting decisions without evidence can derail even the most well thought-out plans. Tom Greever, author of Articulating Design Decisions, calls these hijacking decisions the CEO Button.

An unusual or otherwise unexpected request from an executive to add a feature that completely destroys the balance of a project and undermines the very purpose of a designer’s existence.

You can’t stop requests from sales or support teams reacting to one or two customer requests. You can’t stops requests from the HiPPO — Highest Paid Person’s Opinion. But you can have the tools in place to say, “I’d love to help you but it’s not aligned with our vision, strategy or roadmap. So, no.”

Removes The Emotion From The Decision

When people have something personal invested in an idea or feature that’s on the chopping block, emotions can run high. These are not just unattached ideas or ownerless features, they are reflective of people’s personal hard work.

Having a set of proof points that map to your product vision and roadmap eliminates the subjectivity of these tough conversations. Having agreement on the big picture means a much higher likelihood of agreement on a hot button feature.

Encourages Objective Decisions Over Group-Think

In spite of your efforts to develop a vision and a roadmap, stalemates can still occur even when the team is aligned on the vision. The key to breaking a potential stalemate is to not set consensus as the goal. Collaborating toward a solution doesn’t require consensus.

Treating everyone on the team as equal human beings doesn’t mean you have to find consensus on everything. Collaboration also means healthy conflicts of opinion constrained by a shared vision.

A good team does a lot of friendly front-stabbing instead of backstabbing. Issues are resolved by knowing what they are. — John Maeda

The job of the product leader is to help the team rise above thinking of only their individual contributions and consider higher goals.

Final Thoughts

Prioritization never really ends. As soon as you are done, you need to start collecting new data, analyzing changes, and reviewing plans. Anything that has to do with humans is inherently temporary. Set the expectation for a rolling prioritization schedule with your team and you’ll find things run just a little smoother.