Humans need to get stuff done.

All day, and unfortunately, most nights, our brains auto-update a list of tasks, to-dos, needs, and wants. Good or bad, having things on your task list creates stressors.

Your body can’t differentiate between good and bad stress. Every time you add something to your “I gotta get this done” list, you add a little bit of stress. This stress can be helpful, when it’s a motivator, or bad, when it’s an anxiety creator. As product creators we need to understand how our users employ our products to manage their stress.

Whether humans are mowing the lawn, paying the bills, packing a healthy lunch for the kids, organizing vacation photos, working with co-workers, or trying to make their commute more effective, they are constantly seeking helpers to get those things done. These helpers are your products.

Hiring your product to create outcomes

Products and services are the vectors to outcomes. When you mow the lawn, you “hire” the cordless mower‘s grass-cutting features to achieve that goal. The mower might get the lawn trimmed, but the real job it’s performing is leaving you with a sense of satisfaction (task completed = dopamine rush) and even pride (taking care of my home = serotonin rush). These outcomes are the real Jobs To Be Done (JTBD) that your product fulfills.

JTBD are not feature lists. When utilized correctly, JTBD describe the outcome achieved by that feature or experience. They transcend the activity and focus us on the end state that’s created when that task is completed.

The JBTD format focuses on the why behind the task or activity.

Don’t design what people want. Design what they need

Product companies are a little data obsessed, but data is just a rear-view mirror unless you connect it to users’ needs and desires. Most companies can tell you the exact age, race, marital status, salary, and lifestyle preferences of their target customers but many can’t tell you why their customers buy from them. Big data, we have a problem.

We’re also gathering the wrong data. Simply interviewing your target customers so you can listen to their wishes for fancy new colors, features, and functions gets you nowhere. The pioneers of JTBD theory, Christensen, Hall, Dillon, and Duncan, suggest that this misalignment of data gathering and user needs is a ubiquitous problem.

“Jobs aren’t just about function — they have powerful social and emotional dimensions” — Christensen, Hall, Dillon, & Duncan

People are way more than their profiles

Demographic data can be dangerous because it creates a local maximum. The data says our clients are XYZ so that must be all they are. Demographic data completely ignores the true root of the customer need. In their HBR article, Christensen, Hall, Dillon, & Duncan provide the example of a struggling condo developer.

The developer had the typical market-level metrics on their target. Described as a “retired, downsizing customer”. In-depth interviews with actual customers were conducted to inquire about the most appealing features of their units. The developer listened and added bay windows, “squeak-less” floors, and larger second bedrooms.

Sales were lackluster.

From features choices to lifestyle impacts

An innovation consultant was brought in to dig deeper and ask the right questions. Rather than keeping the conversation on features, he dug into the why, the true emotional and psychological circumstances surrounding a home purchase. He discovered that the decision to buy a condo had very little to do with squeaky floors, bay windows, or pool access.

Moving house is a traumatic experience for most. A longer list of condo features can’t change the way we feel about that change unless they change the outcome of the experience too. Image by Grant Lemons on Unsplash

Rather, it had everything to do with the difficulties of “moving a life.” Where will I put the kitchen table? Will we make new friends? Does the couch stay or go? How can I give up the desk my daughter did homework at every night for 10 years?

The new insight transformed the job to be done of these home buyers from “buying a condo” to “moving a life.” With this newly shaped JTBD, the developer shifted the focus to offerings that would ease the pains of relocating.

They included the cost of 2 years of storage space, offered “sorting” rooms where people had time to make decisions about what furniture would stay and go, and they even made space in the units for the beloved family kitchen table that held so much meaning to retired couples.

The result: 25% sales growth at a time when industry sales were down 49%.

“Jobs To Be Done identifies not just what a user wants done, but also why.” — Chris Tucker, Project Manager

When you are myopically focused on the task/function/feature, you are missing the opportunity to serve your customer’s true need.

So often, serving that need also becomes your competitive advantage.

As Zbigniew Gecis reminds us, if Henry Ford focused on the task of “building a faster horse”, he never would have served the true JTBD of “getting from point A to point B as quickly as possible.”

Real-world example of how to use JTBD

The organization

The product organization in this example is an educational non-profit leading the charge in school district transformation.

The user

The customers are teachers and school administrators.

The customer problem

The general problem area that this organization is trying to solve is the one of time, or the scarcity of it. Teachers and school administrators complain that they don’t have enough time to find the resources they need to be more effective at their jobs.

The intended solution

This website needs to make the process of finding the right resource at the right time feel seamless.

The product team’s task

The broad UX task of the product team is to design an engaging navigation and interaction model for the company website that could connect users to the best tools to address their needs.

“A Job to be Done is neither found nor spontaneously created. Rather, it is designed.” — Alan Klement

Let’s get to work

When considering JTBD, the work always starts in the same place — with the end user. Rather than simply asking users, “what features or functions do you want in this tool?” UX designers or researchers explore what types of tasks they need to accomplish so they can achieve an outcome. Researchers then investigate why those specific tasks are necessary or whether alternatives exist.

By understanding a user’s motivations as well as their desired outcomes, UX designers/researchers can begin to develop the empathy needed to design relevant experiences.

Here’s the JTBD format:

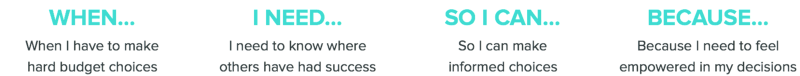

And with a little more detail… “When [I’m in this situation], I need [to do these things], so I can [create these outcomes], because [those things make me feel this way].”

When answered by administrators, these Mad-Lib style sentences reveal that they need additional input from others before making their decision.

JTBD are a little like the Five Why’s because it quickly peels back the layers and exposes the motivation behind the actions or needs.

In our example, the JTBD here is not simply “to make budget cuts.” Adding in a feature to help trim budgets, which sounds superficially useful but is not customer-centric, might actually create anxiety and uncertainty for school administrators.

This is the breakthrough knowledge.

Tough decisions are never easy

Why is this the case? It turns out that not all districts and schools face the same type of budget challenges. Analyzing user feedback in the JTBD format suggests that for the school admins to feel good about their budget changes, they seek experience and wisdom from others who have found success under similar conditions. Gathering this wisdom is a key point of reference for administrators to gather before making their own budget decisions.

Refining the JTBD provides additional clarity…

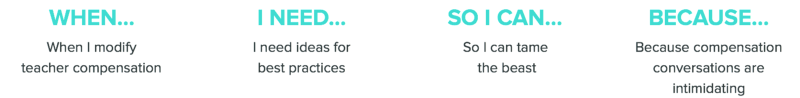

If the product team had focused merely on tasks, this could lead to the shortsighted description: “I need to modify teacher compensation.” That would have been a big fail.

The insight that JTBD provided

By listening closer, it’s now clear this JTBD has little to do with just the salaries and budgets. School administrators are looking for the wisdom of their peers, best practices, and for strategies that have proven to be successful in smoothing out the tough conversations surrounding compensation.

Once identified, this insight might be translated into product design experience as a feature set that allows for sharing knowledge on the website. A place for the sharing of success stories, experiences, case studies, and best practices to help inform and empower peers to make difficult decisions. Designers can now develop hypotheses and testable prototypes to learn if those features provide a solution for the users.

Tying it together

This example sheds light onto how JTBD are used in the wild. When discovery is done correctly, the JTBD tool can create insights, empathy, get to the why at the root of user needs, and uncover the ideal next step for your product or service.

Helping your user manage their stress is a core consideration for UX design. Connecting a solution to a desired outcome only works if the user walks away feeling like some part of their stress has been relieved. JTBD connect the utility of your product to the user’s ability to manage their stress.

These insights prioritize design efforts, inform the roadmap, and provide a reliable gut-check when you’re pondering what to build next. Don’t get tied up in distracting data or surface responses. Dig deeper and stay committed to the why (or whys)and you’ll have a product or service that is valuable.

Hungry for more product design tips?

Download two free chapters of Design Sprint: A Practical Guidebook for Building Great Digital Products.