Experience mapping has become a very popular approach to visualizing and aligning an organization around the experiences they are creating for their customers. A simple Google search will reveal several types of maps, however, they can only be useful if you know what each is designed to accomplish and which to use when. Journey Maps, Experience Maps, and Service Blueprints are three common visualization tools and strategies that look very similar and work to accomplish similar objectives, but they have different applications. Knowing the difference between these tools is similar to knowing the difference between a flathead, a phillips head, and a hex head screwdriver. Choose the right tool and it will make your objective significantly easier to achieve. Choose the wrong tool and you may not fully accomplish what you set out.

You can read the extended version below or if pressed for time, you can jump to the essential takeaways

People often confuse and interchange these maps when discussing and labeling them. Although somewhat different, maps and blueprints each help to build a holistic, end-to-end picture of a user experience. Each of them includes a different point of view, scope, and focus, but the point in constructing them is the same — to identify opportunities for improvement in a product or service.

Timing is Everything

Maps and Blueprints should be considered at three different stages of product development.

- When an offering is beginning to hit critical mass. Most startups adapt their product for each new customer they can sign on. While this approach is necessary to get off the ground, there comes a time when it can no longer scale.

- When a more mature product needs a more strategic approach. It’s very easy for a seasoned product to fall into the trap of constantly playing catch up with a backlog of user requests. Maps and blueprints allow product owners to make the case for a more deliberate and more forethoughtful approach to product development.

- When a product is approaching a rebuild. Before diving into a 2.0 effort, it is wise to take a step back and analyze the current experience from a comprehensive point of view.

Anatomy of a Map

As the name suggests, maps document a course from one place to another highlighting milestones, obstacles, and alternate paths along the way. They both focus on the current (flawed) state of an experience, not the future (idealistic) state.

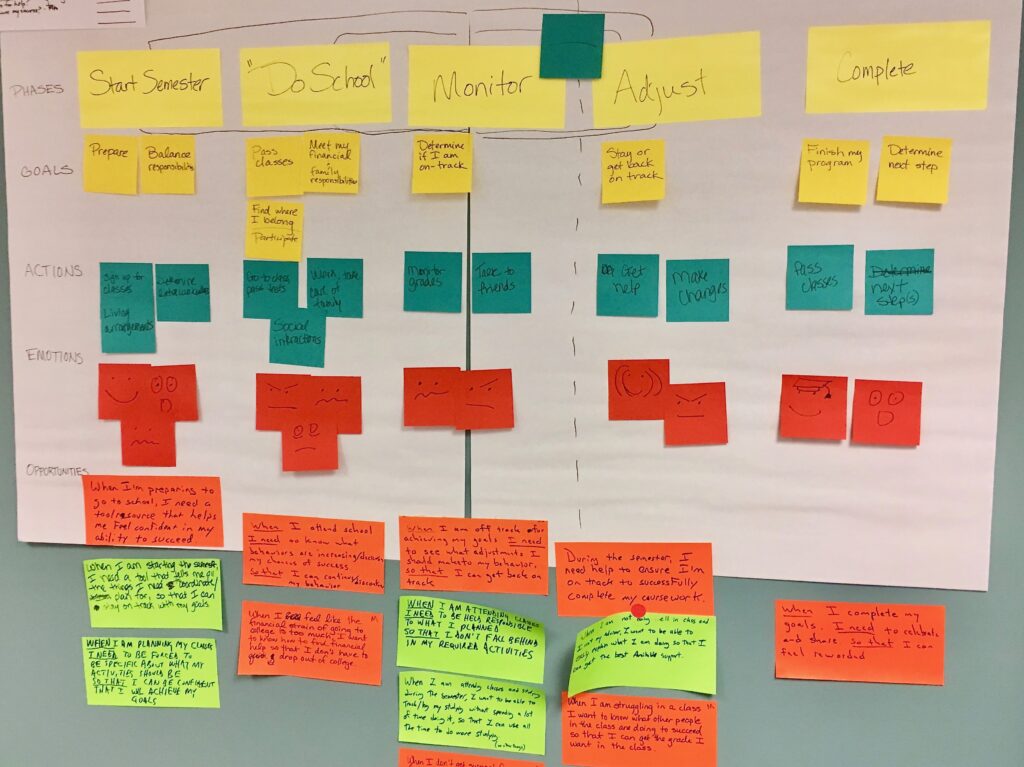

Let’s start with basic map anatomy. Maps should always include stages, goals, emotional state, and pain points/opportunities.

Stages: major chapters and milestones

ex: discovery

Goal(s): what the stakeholder wants to accomplish at each stage

ex: drive impressions

Emotional State: the reactive sentiment of the stakeholder at each stage

ex: user is feeling uncertain

Pain Points/Opportunities: aggravations identified as part of the experience (Opportunities are pain points reworded as How Might We… statements.)

ex: C2A is unclear (or, How might we make the C2A clearer?)

Maps can optionally include additional swimlanes like user actions, logistics/channels, compelling forces or other custom dimensions.

User Actions: tasks a stakeholder must take to progress to the next stage

ex: upload contacts

Logistics: channels, locations, or tools a stakeholder uses to accomplish their actions

ex: Excel

Compelling Forces: the external and internal pushes and pulls a stakeholder experiences when making choices at each stage in the experience (based on Bob Moestra and Chris Spiek – Forces of Progress)

ex: upcoming off-season

Custom Dimensions: any other measurable aspect specific to your experience

ex: trust

Journey Maps vs. Experience Maps

Some distinguish between the two maps by what part of the user experience they cover:

- Journey maps cover the path from discovery of a need/desire through to finding brands and products appropriate, to purchase (essentially, the journey up to becoming a customer).

- Experience maps include the customer journey (from need discovery through finding brands) but also including the time through ownership, usage, service, support, recommendations, reviews, references, responses and referrals (essentially the full experience of a customer).

At Fresh Tilled Soil, we consider them as part of the same timeline — encompassing the entirety of the experience from before a user is aware of a pain/need, through solution discovery, to after they are done using it. Where we split the two maps is in the point of view/perspective, the depth of detail they include, and the validation they require.

Journey Maps

Journey maps typically view the individual as a customer of the organization. They are drawn from the perspective of the customer only. They are unique in that they are more brief and only include one, generic stakeholder perspective. This means when referring to the stakeholder, the map could be alluding to multiple people depending on the stage or user actions. For example, the buyer and the user are often different people when mapping enterprise software but in this case they get lumped together into one representative “customer.” If there are points in the journey where customers have varying reactions, a simple branch in scenarios is made without trying to assign or organize that branch of behavior to a particular user group.

One advantage of a journey map over an experience map is the amount of time investment required. If you need an expeditious way to get things moving, journey maps can usually be charted in two or three hours. For this reason they are a popular tool during the Understand phase of Design Sprints, however they are not restricted to use within the entirety of a Design Sprint. The downside, of course, is lack of depth. Because it genericizes the stakeholder it can overlook the insights you would get by examining a unique user set.

On rare occasion journey maps can be employed to chart out a future state of a not yet existing product or service which helps a team to understand what might need to be considered in the design process. However, these future facing journey maps tend to be more idealistic than realistic so use with discretion.

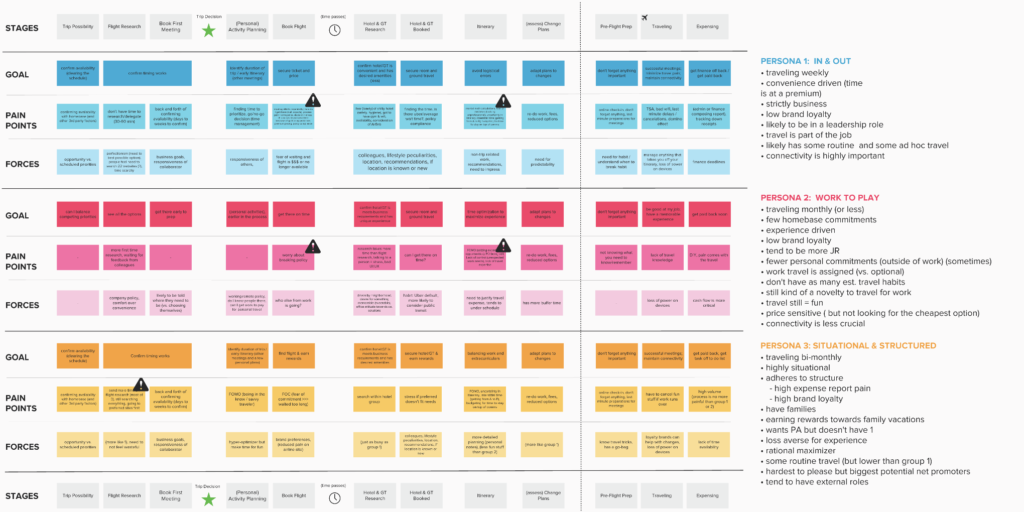

Experience Maps

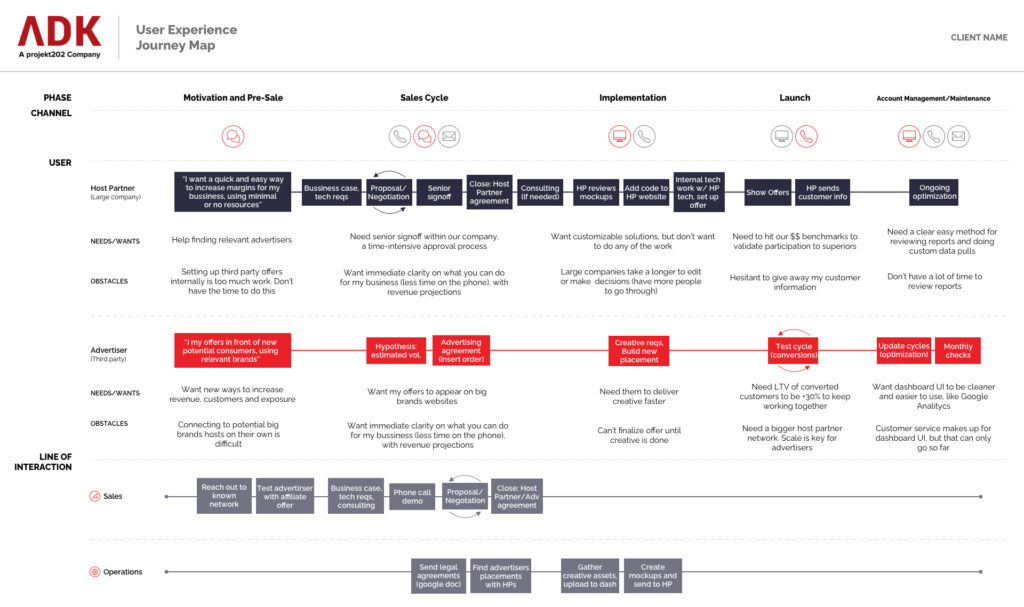

Experience maps include all the touch points from both the customer and business perspective. They provide an objective view of all interactions. They also include multiple personas. One thing to remember when executing this effort is not to confuse personas with roles. It can be valuable to include different user roles (ex: buyer vs. daily user) however, your best insights are going to come from examining personas based on behavioral characteristics (ex: frequent diner vs. special occasion diner).

Another thing that distinguishes experience maps from journey maps is the amount of research and polish that goes into the composition of the experience map. While journey maps are a quick-get-started tool, experience maps go through a validation process to ensure that elements were not overlooked or incorrect assumptions made. This validation occurs after the experience maps have been developed to ensure their integrity. The additional work to research and validate experience maps can cause them to take a week or two complete, longer than the journey map but still shorter than most development sprints, which makes them a very reasonable strategic activity to attempt.

The output of an experience map, similar to journey maps, is to illuminate opportunities for improvement. They can also be used as an internal communication tool for companies who want to demonstrate to employees how each contributor impacts the bigger picture. While some organizations use experience maps to capture a snapshot in time of an offering experience, they can also be treated as living document, updated regularly as the experience evolves.

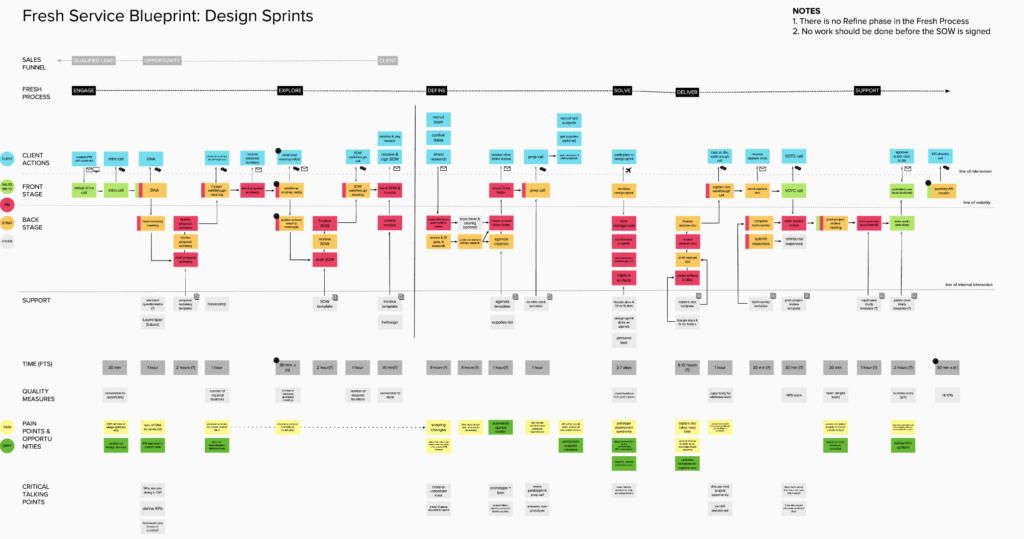

Service Blueprints

A distinct feature of blueprints is that they are internally-focused. They view how a service is experienced by a customer. Much like an architectural blueprint details the construction and inner workings of a building, a service blueprint illustrates many layers of supporting structural components of a single solution. Service blueprints are especially helpful if you are looking for ways to reform internal systems in an effort to cut costs or provide a superior offering. They are an ideal approach to experiences that are omni-channel, involve multiple touch-points, or require a cross-functional effort (e.g., coordinating multiple departments). As the name indicates, they are a better tool for pure service offerings or hybrid product/service offerings than for pure products.

Like maps, service blueprints contain stages (sometimes a limited set) and user actions, however they also contain several tiers of actions by the organization offering the product or service. This includes frontstage actions, backstage actions, and supporting services.

Frontstage Actions: performed by the organizations that the user can clearly observe through touchpoints

ex: deliver contract

Backstage Actions: performed by the organization that the user cannot directly witness

ex: composition of contract

Supporting Services: third party services an organization employs to perform a certain task

ex: digital contract signing

Time: actual or expected time to complete action or stage

ex: 20 minutes

Quality Measures: KPI or other internal metric by which to quantify success

ex: number carts abandoned per sales completed

Additionally, internal metrics like time and quality measures can also be added to add a quantifiable element to a service blueprint. Whereas user roles or personas are detailed in maps, organizational departments or teams are specified in the service blueprint. This helps to understand the flow of information and responsibility between internal teams.

Another unique step in blueprinting is to detail the flow of actions and how each one relates to another. Not only are you organizing actions by different groups along a timeline, you are connecting them to each other, dictating order and often times including how information or responsibility is transitioned from one party to another.

At Fresh Tilled Soil, we did our own blueprinting of the process behind our Design Sprint offering.

After completing our blueprint we realized that we were not doing all we could to help set expectations for Design Sprint participants. Since then we’ve instituted a pre-sprint webinar with all those who plan to take part in an upcoming Design Sprint and it has had a significant impact on setting expectations for the week and starting strong on day one. We also realized that a new Keynote was being created for every new Design Sprint. We’ve created one master Design Sprint facilitation deck that can be copied and customized for each Design Sprint, saving us approximately six hours of prep time per engagement.

Essential Takeaways

- Employ a Journey Map, Experience Map, or Service Blueprint effort when you want to take a strategic approach to product management or product redesign. It’s a small enough effort to fit into a single design or development cycle and can help set the right perspective for a longer series of work.

- All three tools chronicle the user experience in a holistic snapshot and highlight opportunities for improvement.

- Journey maps are quick (1–2 hours), simpler, and contain only the lens of a single, generic user. You should use a journey map if you know where you want to focus or if you know the source(s) of most of your customer’s friction. (e.g., the checkout process of a retail website)

- Experience maps contain more detail, the perspectives of multiple personas, and are validated for assurance. You should use an experience map if you don’t know exactly where the problem is. (e.g., online sales of a retail website are dropping, and you want to discover where/why)

- Service blueprints examine the internal processes used to deliver on a customer experience.